By Mark Mazzola

By Mark Mazzola

The federal Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) recently finalized new rules for the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which became effective on September 14, 2020. This was the first major revision to NEPA in over 40 years. The impetus for the updated rules is to streamline the NEPA process, which is often subject to delays from lengthy decision-making processes and litigation. The CEQ found that it takes an average of 4.5 years to complete a NEPA environmental impact statement (EIS) process, from a notice of intent to the issuance of a record of decision, with many projects taking over 10 years to complete their EIS process. The new regulations are meant to clarify and codify what is already required by NEPA, its implementing regulations, guidance, and case law (Venable 2020a).

Following is a summary of the major changes to NEPA made by the new rules. The discussion is taken primarily from articles and presentations from Venable and Van Ness Feldman, as well as from the final rule summary and language as published in the Federal Register. Federal agencies are currently working on updating their own implementing regulations and guidance; however, they are incorporating the new NEPA rules to varying degrees on current and new projects. Project managers and environmental staff should coordinate with their respective federal lead agency while undergoing any new NEPA process.

Major Federal Actions

While there has been much talk of page limits and duration in which NEPA reviews should be conducted, one of the major changes is what is now considered a “federal action” under the rule. The new rule redefines what constitutes a “major Federal action” and therefore what triggers NEPA. Under the new rule, for example, “Non-Federal projects with minimal Federal funding or minimal Federal involvement where the agency does not exercise sufficient control and responsibility over the outcome of the project” would not be subject to NEPA review (CEQ 2020, section 1508.1 (q)(1)(vi)). This could have implications for projects funded by federal grants where the federal funding isn’t considered substantial, thus reducing the number of projects that are required to undergo NEPA review as compared to the previous rule.

The new rule codifies other federal actions that have, through various judicial decisions, been commonly understood to not require NEPA review, including “Activities or decisions that are non-discretionary and made in accordance with the agency’s statutory authority” (CEQ 2020, section 1508.1 (q)(1)(ii)). This is consistent with the CEQ’s thought and case law that NEPA should not be required where it cannot influence the outcome to address the potential effects of a project (Venable 2020b).

Agency Coordination, Scoping, and Alternatives

The new rule codifies the One Federal Decision policy under Executive Order 13807 for federal agencies that have discretionary decision-making authority for a project to coordinate on schedule and, if able, to issue a single environmental document. This document would then be relied on for a joint record of decision or finding of no significant impact as well as for other permitting or authorization decisions. The final rule also allows agencies to adopt other agencies’ categorical exclusions[1] (Van Ness Feldman 2020a). This should streamline federal approval processes and result in more predictability for the environmental process when multiple federal agencies are involved.

A notice of intent must now include a description of the proposed action and alternatives the EIS will consider, as well as a brief summary of expected impacts (CEQ 2020, section 1501.9(d)). The new rules clarify that alternatives must be technically and economically feasible, meet the purpose and need of the proposal, and be under the jurisdiction of the agency. Since the time limit for completing an EIS is triggered by the issuance of the notice of intent (more below), an agency can effectively stretch out the time frame by conducting more analysis up front to collect data, conduct some early analysis, and narrow the range of alternatives prior to scoping (Van Ness Feldman 2020a).

The new rules also change the list of factors to consider when determining whether a proposal’s impact may be significant. For example, the proximity to historic or cultural resources and ecologically sensitive areas has been removed, as has the consideration of whether the proposal is highly controversial (Venable 2020a). Agencies are now to consider the short- and long-term effects, beneficial and adverse effects, effects on public health and safety, and effects that would violate federal, state, tribal, or local law protecting the environment (CEQ 2020, section 1501.3(b)). While this would provide more flexibility to project proponents in assessing significance, it would likely result in fewer determinations of significance, particularly with the removal of public controversy as a factor to consider.

More controversial, however, is the elimination of the concepts of direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts. Instead, the new rules focus the analysis on those effects that are “reasonably foreseeable” and those that “have a reasonably close causal relationship to the proposed action or alternatives.” A “but-for” analysis is no longer sufficient, and effects should generally not be considered if they are remote in time or geography (Van Ness Feldman 2020a; Venable 2020a). Associated with this change is a concern over the fact that the new rule arguably weakens the requirement to evaluate the effect of proposals on climate change. While climate change trends are allowed to be discussed as part of the description of baseline conditions, the CEQ states that they would not be discussed as an effect of the action (Venable 2020a, CFQ 2020).

The new rule also codifies the current practice that project sponsors (and their consultants) can prepare an environmental assessment (EA) or EIS under agency supervision; agencies remain responsible for providing accuracy, guidance, and independent evaluation (Venable 2020b). This is already the practice in Washington state for many of our transportation projects where the Federal Highway Administration and the Federal Transit Authority delegate responsibility for NEPA compliance to state and local agencies, such as the Washington State Department of Transportation, Sound Transit, and local departments of transportation.

Timelines and Page Limits

Under sections 1501 and 1502, CEQ has established new timeline and page limits for EAs and EISs, although both of these can be extended by the federal lead agency (CEQ 2020). Proponents will have one year to complete an EA and two years to complete an EIS; time is measured between the issuance of a notice of intent and publication of the finding of no significant impact or record of decision. EAs are capped at 75 pages, while EISs are capped at 150 pages or 300 pages for proposals of “unusual scope or complexity” (CEQ 2020). The page limits do not count supporting or technical appendices that may be attached to the documents.

Tribal Involvement

The new NEPA rules make a number of revisions to better integrate tribal involvement, including a recognition that tribes may assume responsibility for implementing NEPA and be considered cooperating agencies. Agencies are required to coordinate with affected tribes in establishing NEPA review timelines and coordinate with tribes on the analysis of effects on tribal lands, resources, or areas of historic significance. Further, the new rule recognizes that tribal interests are not just limited to reservations (Van Ness Feldman 2020a).

Public Involvement and Consideration of Comments

The new rule retains the 45-day minimum public comment period for a draft EIS and a 30-day waiting period between publication of the final EIS and the record of decision. Agencies now have the option to allow public comment during this 30-day waiting period. In addition, the new rules update the means through which agencies interface with stakeholders and the public, such as allowing electronic forms of communication for making information available to the public, conducting outreach and public notification efforts, accepting comments, and structuring public participation (CEQ 2020).

Other rule changes concerning public involvement have caused concern over the fact that they restrict public participation in the NEPA process and the ability to challenge an agency’s analysis, which could particularly affect disadvantaged or disenfranchised communities (Venable 2020a, 2020b). The new rules expand requirements over the specificity and detail needed in public comments and require that comments or objections by the public, including by federal, state, tribal, and local agencies, must be submitted during public comment periods or be “forfeited as unexhausted.” In other words, an interested party cannot bring up an issue in subsequent litigation unless they first identified the concern during an established comment period. Further, commenters must rely on their own comments and not those submitted by other commenters in any litigation (Venable 2020a, CEQ 2020).

A new section is required that summarizes “all alternatives, information, and analyses submitted by interested parties” on the notice of intent and draft EIS as a means to ensure that the agency has identified all relevant information submitted by commenters (CEQ 2020). The new rule requires the decision maker to certify in the record of decision that the agency has “considered all the alternatives, information, analyses, and objections” submitted; if certified, the agency is entitled to a presumption that it has adequately carried out its requirements under NEPA (CEQ 2020, Venable 2020a).

Remedies

A new Remedies section limits the basis for injunctive relief for minor or non-substantive errors, stating that errors that have no effect on agency decision making would be considered harmless and would not invalidate an agency action. The new section also allows that failure to comply with NEPA, as a procedural statute, can be remedied by compliance with NEPA’s procedural requirements, and that it is CEQ’s intention that the NEPA regulations “create no presumption that violation of NEPA is a basis for injunctive relief or for a finding of irreparable harm” (CEQ 2020, section 1500.3(d)). These changes could mean that projects would be less likely to be delayed due to procedural errors alone because it must be shown that the lead agency, for example, made substantive errors or irreparable harm would occur without an injunction. However, the effect of the new remedies section will ultimately be determined by the courts as they make decisions about what constitutes harmless errors under the new law (Venable 2020a).

Challenges Ahead

The new NEPA rules became effective in September. However, implementing federal agencies have an additional year from that date to update their own regulations. While this is underway, agencies are taking different approaches to work on current and upcoming projects, and sponsors should check on what is required. As prior CEQ guidance has been superseded, CEQ plans to withdraw old guidance and publish new guidance to replace it (Venable 2020a).

The new rule is subject to the Congressional Review Act and could therefore change due to further reviews in Congress or if there is a change in administration as a result of the 2020 federal elections (Venable 2020a). In fact, there are two bills currently pending in the Senate for further NEPA amendments (Venable 2020b).

Adding more uncertainty are the number of legal challenges facing the new rule. Three major coalitions of environmental groups, led by the Southern Environmental Law Center, Earthjustice, and the Natural Resources Defense Council, filed challenges in Virginia, California, and New York respectively. In addition, a coalition of over 20 state attorneys general, led by California and Washington, filed suit in San Francisco (HHF 2020). The suits challenge the new rules as arbitrary and capricious, arguing that the rules violate the statute it implements by failing to develop an EA or EIS, and that the removal of the cumulative impacts requirement will prevent the consideration of effects on environmental justice populations (Van Ness Feldman 2020b).

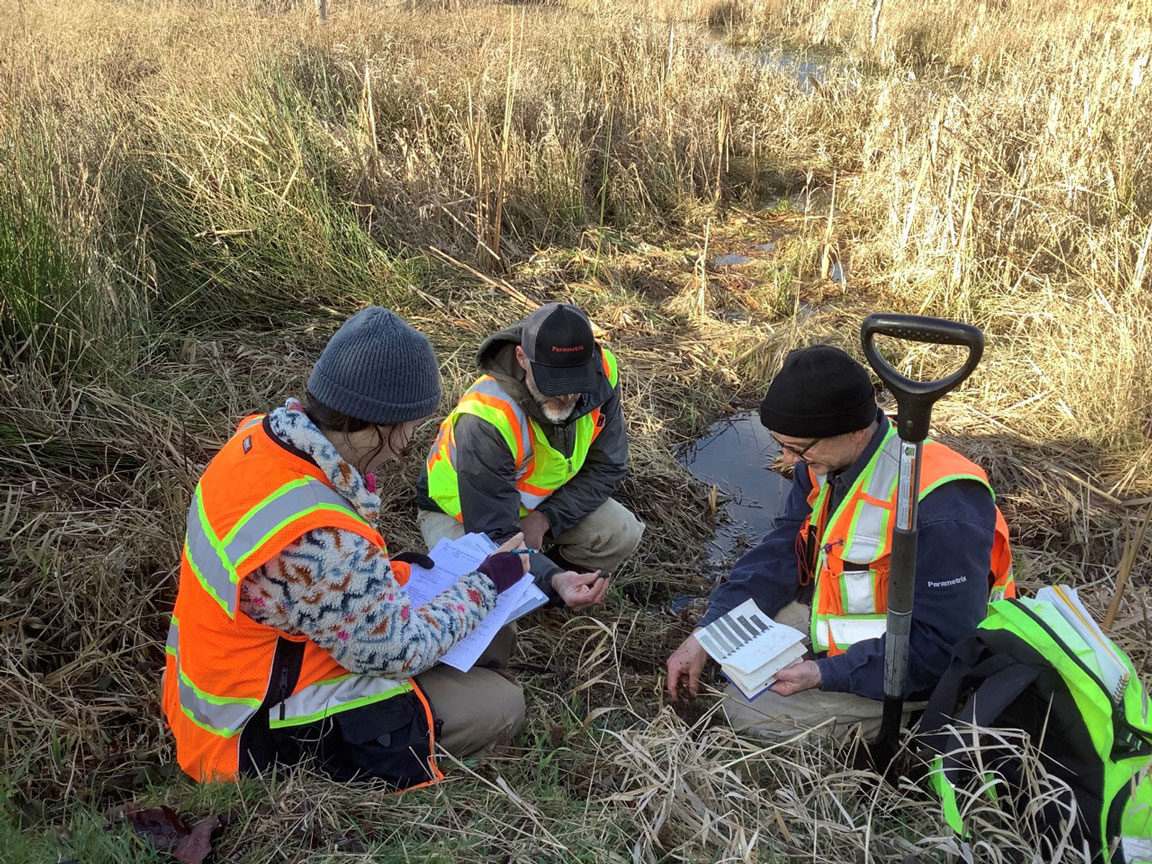

Learn more about Parametrix’s expertise and experience in environmental documentation here.

References

Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ). 2020. Update to the Regulations Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act. Federal Register, Vol. 85, No 137. July 16, 2020. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-07-16/pdf/2020-15179.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Historic Hawaii Foundation. 2020. National Coalition Files Lawsuit to Challenge New National Environmental Policy Act Regulations. August 29, 2020. Available at: https://historichawaii.org/2020/09/04/national-coalitions-files-lawsuit-to-challenge-new-national-environmental-policy-act-regulations/. Accessed October 12, 2020.

Van Ness Feldman LLP. 2020a. CEQ Issues Final Rule to Modernize NEPA Regulations. July 20, 2020. Available at: https://www.vnf.com/ceq-issues-final-rule-to-modernize-nepa-regulations. Accessed October 12, 2020.

Van Ness Feldman LLP. 2020b. Environmental Groups Challenge Final NEPA Rule. August 7, 2020. Available at: https://www.vnf.com/environmental-groups-challenge-final-nepa-rule. Accessed October 12, 2020.

Venable LLP. 2020a. CEQ Finalizes Amendments to NEPA Regulations, but Challenges Lie Ahead. July 29, 2020. Available at: http://venable.com/insights/publications/2020/07/ceq-finalizes-amendments-to-nepa-regulations. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Venable LLP. 2020b. CEQ’s Amended NEPA Regulations: What’s Old, What’s New, and What to Expect. Presented through “Changes to NEPA Implementing Regulations and the Potential Impact on A/E Firms and Clients” webinar hosted by the American Council of Engineering Companies, September 30, 2020. Available for purchase at: https://education.acec.org/diweb/catalog/item?id=5924533. Accessed October 9, 2020.

[1] Categorical exclusions are actions or decisions that an agency has shown not to have significant adverse environmental affects and therefore do not require review under NEPA.

About the Author

Mark Mazzola is a senior planner at Parametrix based out of Seattle, WA. He has extensive experience leading SEPA and NEPA environmental reviews for public transportation projects. Prior to joining Parametrix a year ago, Mark served as the environmental manager for the Seattle Department of Transportation. He served as the department’s SEPA Responsible Official and led the environmental services group responsible for the environmental review and permitting for the department’s transportation, transit, and infrastructure improvements.